INTRODUCTION

The American Cancer Society makes estimates of the number of new cancer cases and deaths every year. Cancer mortality continued to decline through 2021, with more than 4 million deaths avoided since 1991 due to reductions in smoking, earlier detection of certain cancers, and improvements in adjuvant and metastatic treatment regimens in the United States1. Lung cancer is one of the most commonly diagnosed cancers globally and is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide, with an estimated 2 million new cases and 1.76 million deaths annually2. Lung cancer has been identified as one of the cancers most significantly influenced by smoking, which is a major risk factor for cancer development and closely related to its diagnosis and treatment3.

Nowadays, increasing attention has been paid to the mental health status of lung cancer patients, particularly the prevalence of depression, which is closely related to the treatment of lung cancer patients4. Addressing the depression in lung cancer patients has positive implications for improving their mental health and treatment, as well as alleviating the distress during survival5. Additionally, smoking, a significant factor related to lung cancer, is also closely associated with depression, and genetic susceptibility to depression could increase the likelihood of smoking6.

Emerging evidence suggests that smoking may act as a bidirectional mediator between depression and lung carcinogenesis7. On the one hand, nicotine dependence could exacerbate depressive symptoms through neuroinflammatory pathways8. On the other hand, depression-related cognitive impairments may hinder smoking cessation efforts9. However, three critical gaps persist. First, most studies focus on pairwise associations (smoking-cancer or smoking-depression), neglecting their synergistic effects. Second, the moderating role of demographic factors remains underexplored. Third, population-based evidence integrating biochemical markers is scarce.

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) provides a unique opportunity to investigate these relationships in a nationally representative population10. Building on prior evidence of smoking-depression comorbidity, we hypothesize that quitters will exhibit higher depression prevalence than never smokers, reflecting withdrawal-related mood dysregulation and that smoking status mediates the depression-lung cancer association through both biological and behavioral pathways. This study aims to test these hypotheses by characterizing population-level patterns and quantifying mediation effects, leveraging NHANES’s strengths: nationally representative sampling, standardized mental health assessments, and biochemical validation of smoking status.

METHODS

Data source

This secondary dataset analysis utilized pooled data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2005–2016, a nationally representative cross-sectional survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). NHANES employs a complex, multistage probability sampling design to ensure generalizability to the non-institutionalized US population. The survey integrates interviews, physical examinations, and biological specimen collection, with ethical oversight provided by the NCHS Research Ethics Review Board (Protocol #2005–06 and subsequent continuations).

Data processing

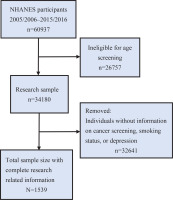

Data processing and analysis were performed using R software with the dplyr and survey packages. We obtained demographic, lung cancer, smoking status, and depression screening (PHQ-9) data for the 2005–2016 cycles from the NHANES database. Data from different years were merged to create a unified dataset. To account for the complex survey design of NHANES, we created a weighted analysis object incorporating sampling weights, stratification variables, and primary sampling units. Participants were screened according to the following eligibility criteria: age ≥20 years; complete data on depression status (assessed by the Patient Health Questionnaire-9, PHQ-9); documented cancer diagnosis history (self-reported or medically confirmed); and exclusion of pregnant women and individuals with incomplete demographic/clinical covariates. Participants were screened following the steps in Figure 1.

Variable definitions

Smoking status was categorized as: 1) Non-smokers – not currently smoking (SMQ040 = 3); and 2) Current smokers – daily/occasional cigarette smokers (SMQ040 =1 or 2). Smoking cessation status was categorized as: 1) Recent quitters – patients that had already quit smoking (SMQ050 = 1–66); and 2) Other –smoking cessation status of these patients was unknown. (SMQ050 = 77777 or 9999). Depression was defined8 by PHQ-9 scores ≥10.

Statistical analysis

All analyses accounted for NHANES’s complex survey design using R’s survey package (v4.1) with the WTINT2YR sampling weights. After confirming data were missing completely at random (tested via Little’s test), we performed multiple imputation11 using chained equations for incomplete covariates, generating 20 imputed datasets. A total of 1539 adults were included in this dataset after applying strict exclusion criteria to the original 60937 respondents, with removal of participants missing critical variables for our analyses, which included lung cancer diagnosis (n=892), smoking status (n=1243), and PHQ-9 depression scores (n=57263). The resulting sample maintained demographic representativeness through NHANES survey weighting, with non-response adjustments applied to preserve national population estimates.

Weighted prevalence estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using the Korn-Graubard-adjusted svyciprop() function. Multivariable logistic regression via svyglm() adjusted for age (20–39, 40–59, ≥60 years), sex, race, education level, income-to-poverty ratio, and comorbidities. Variance was estimated using Taylor linearization.

Effect modification was assessed through Wald tests of interaction terms. Sensitivity analyses included complete-case comparisons and multicollinearity diagnostics (VIFs <2.5).

RESULTS

Study population

The final analytic study population comprised 1539 adults (55.7% male, 44.3% female; age range 20–85 years, with a mean age of 65.4 ± 24.1 years) selected from NHANES 2005–2016 (Table 1).

Lung cancer prevalence

Weighted analyses revealed a 3.14% (95% CI: 2.78–3.55) overall prevalence of self-reported lung cancer diagnosis. Subgroup evaluations showed gender disparities as males exhibited a 3.97% prevalence (OR=0.62; 95% CI: 0.34–1.13; AOR=0.58; 95% CI 0.30–1.12; p=0.114). The attenuation of the odds ratio after adjustment suggests potential confounding by age or comorbidities. Multivariable models adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, income-to-poverty ratio, and comorbidities (COPD, cardiovascular disease) to control for socioeconomic and health status confounders. Current smokers showed marginally lower prevalence (AOR=1.21; 95% CI: 0.67–2.18; p=0.515). Full stratified estimates are available in Table 2.

Table 2

Distribution of lung cancer prevalence with adjusted odds ratios, NHANES 2005–2016 (N=1539)

[i] AOR: adjusted odds ratio. Multivariable models adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, income-to-poverty ratio, and comorbidities (COPD, cardiovascular disease). Crude ORs derived from univariate logistic regression. Smoking status was categorized as: 1) Non-smokers – not currently smoking (SMQ040 = 3), 2) Current smokers – daily/occasional cigarette smokers (SMQ040 = 1 or 2). Smoking cessation status was categorized as: 1) Recent quitters – patients that had already quit smoking (SMQ050 = 1–66), 2) Other – smoking cessation status of these patients was unknown (SMQ050 = 77777 or 9999). ® Reference categories.

Current smoking patterns

Current smoking prevalence reached 29.41% (95% CI: 28.02–30.85) in our subsample, with significant demographic differentials as females demonstrated higher odds of current smoking (OR=1.62; 95% CI: 1.34–1.96; AOR=1.97; 95% CI: 1.42–2.73; p<0.05) compared to males. This association persisted after adjusting for age, race/ethnicity, and income, compared to males, contradicting historical sex patterns in tobacco use. Smoking prevalence was inversely correlated with age, peaking at 69.37% (95% CI: 65.12–73.62) in those aged 20–39 years (AOR=1.00, Ref.) and declining to 16.99% (95% CI: 14.67–19.31) in those ≥60 years (AOR=0.12; 95% CI: 0.08–0.17; p<0.001). With regard to mental health associations, individuals with a PHQ-9 ≥10 exhibited higher smoking rates (56.30%; 95% CI: 51.23–61.37) compared to asymptomatic individuals (AOR=3.82; 95% CI: 2.65–5.51; p<0.001) when adjusting for age, sex, and income. Recent quitters constituted only 1.02% (95% CI: 0.65–1.40) of the population, with no significant subgroup variations. This contrasts with the 8.96% prevalence of recent quitters in Table 2, suggesting high relapse rates in this population. Detailed smoking behavior profiles are shown in Table 3.

Table 3

Weighted prevalence and adjusted odds ratios for smoking status, NHANES 2005–2016 (N=1539)

| Variables | Current smokers % (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | Recent quitters % (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 29.41 (28.02–30.85) | 1.02 (0.65–1.40) | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Male ® | 22.46 (18.23–26.68) | 1 | 1.06 (0.27–1.85) | 1 |

| Female | 36.12 (30.79–41.46) | 1.97 (1.42–2.73)* | 0.98 (0.16–1.81) | 0.92 (0.33–2.56) |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 20–39 ® | 69.37 (65.12–73.62) | 1 | 1.85 (0.00–3.92) | 1 |

| 40–59 | 45.76 (41.32–50.20) | 0.38 (0.28–0.52)* | 1.76 (0.85–2.67) | 0.95 (0.31–2.92) |

| ≥60 | 16.99 (14.67–19.31) | 0.12 (0.08–0.17)* | 0.57 (0.20–0.94) | 0.31 (0.09–1.07) |

| Lung cancer | ||||

| Yes | 24.74 (18.23–31.25) | 0.78 (0.45–1.35) | 2.91 (1.23–4.59) | 0.31 (0.09–1.07) |

| No ® | 29.56 (28.12–31.00) | 1 | 0.96 (0.58–1.34) | 1 |

| Depression (PHQ-9 ≥10) | ||||

| Yes | 56.30 (51.23–61.37) | 3.82 (2.65–5.51)* | 2.52 (1.12–3.92) | 2.43 (1.05–5.62)* |

| No ® | 26.03 (24.52–27.54) | 1 | 0.83 (0.51–1.15) | 1 |

AOR: adjusted odds ratio. Multivariable models adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, income-to-poverty ratio, and depression status. Smoking status was categorized as: 1) Non-smokers – not currently smoking (SMQ040 = 3), 2) Current smokers – daily/occasional cigarette smokers (SMQ040 = 1 or 2). Smoking cessation status was categorized as: 1) Recent quitters – patients that had already quit smoking (SMQ050 = 1–66), 2) Other – smoking cessation status of these patients was unknown (SMQ050 = 77777 or 9999). Lung cancer diagnosis includes self-report and medical records.

Depression burden

The weighted prevalence of clinically significant depression (PHQ-9 ≥10)10 reached 11.18% (95% CI: 10.12–12.34). Notable disparities emerged across demographic and behavioral strata. Females exhibited nearly double the depression prevalence of males (OR=2.12; 95% CI: 1.43–3.14; AOR=2.18; 95% CI: 1.63–2.91; p<0.01). This elevated risk persisted after adjusting for sociodemographic and socioeconomic factors. Depression prevalence demonstrated a marked inverse association with age, declining from 25.16% (95% CI: 21.38–28.94) in young adults (18–34 years) to 6.69% (95% CI: 5.42–7.96) among seniors (≥65 years). Compared to young adults, seniors showed 76% reduced odds of depression (AOR=0.24; 95% CI: 0.17–0.34; p<0.001). Compared to non-smokers, current smokers demonstrated tripled depression risk (AOR=3.12; 95% CI: 2.18–4.47; p<0.001). Recent quitters also showed elevated risk (AOR=2.89; 95% CI: 1.15–7.25; p=0.024), though with wider confidence intervals reflecting smaller subgroup size. Comprehensive metrics for all subgroups are presented in Table 4.

Table 4

Weighted prevalence and adjusted odds ratios for depression, by demographic and behavioral characteristics, NHANES 2005–2016 (N=1539)

| Variables | Crude % (95% CI) | Adjusted % (95% CI)† | AOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 11.18 (10.12–12.34) | 10.95 (9.88–12.02) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male ® | 7.34 (5.09–9.59) | 6.89 (4.72–9.06) | 1 |

| Female | 14.88 (12.47–17.29) | 14.12 (11.83–16.41) | 2.18 (1.63–2.91)** |

| Age (years) | |||

| 20–39 ® | 25.16 (21.38–28.94) | 23.87 (20.25–27.49) | 1 |

| 40–59 | 17.19 (14.21–20.17) | 16.54 (13.72–19.36) | 0.62 (0.45–0.85)** |

| ≥60 | 6.69 (5.42–7.96) | 6.32 (5.11–7.53) | 0.24 (0.17–0.34)*** |

| Lung cancer | |||

| Yes | 7.26 (4.31–10.21) | 6.95 (4.12–9.78) | 0.82 (0.52–1.29) |

| No ® | 11.30 (10.20–12.40) | 11.02 (9.94–12.10) | 1 |

| Smoking status | |||

| Current smokers | 21.39 (18.15–24.64) | 20.01 (17.02–23.00) | 3.12 (2.18–4.47)*** |

| Non-smokers ® | 6.91 (5.82–8.00) | 6.32 (5.20–7.44) | 1 |

| Smoking cessation | |||

| Recent quitters | 27.58 (13.84–41.32) | 25.94 (12.95–38.93) | 2.89 (1.15–7.25)* |

| Other ® | 11.01 (9.90–12.12) | 10.78 (9.70–11.86) | 1 |

† Adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, income-to-poverty ratio, and education level. All estimates incorporate NHANES survey weights (WTINT2YR). Smoking status was categorized as: 1) Non-smokers – not currently smoking (SMQ040 = 3), 2) Current smokers – daily/occasional cigarette smokers (SMQ040 = 1 or 2). Smoking cessation status was categorized as: 1) Recent quitters – patients that had already quit smoking (SMQ050 = 1–66), 2) Other – smoking cessation status of these patients was unknown (SMQ050 = 77777 or 9999). Lung cancer diagnosis includes self-report and medical records.

Sensitivity analyses confirmed the robustness of these findings: Complete-case versus imputed models showed minimal parameter divergence (ΔAOR<10% for smoking status effects). All variance inflation factors (VIFs) remained <2.5, indicating absence of multicollinearity.

DISCUSSION

The global burden of lung cancer reflects heterogeneous risk factor landscapes, with smoking prevalence, environmental exposures, and socioeconomic conditions driving regional disparities in incidence and mortality12. While lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide1, our analysis of NHANES 2005–2016 data provides critical insights into the US adult population, demonstrating persistent challenges in smoking control and mental health comorbidity management.

This NHANES analysis reveals three central patterns. Depression was strongly associated with smoking behavior, with current smokers and recent quitters showing 3.12-fold and 2.89-fold higher odds of depression compared to non-smokers. Gender modifies this relationship, as female smokers exhibit 44% greater depression vulnerability than males. Smoking status showed no significant association with lung cancer prevalence in this cohort. However, among the subset with lung cancer, smokers exhibited significantly higher depression burden, while the non-significant statistical association in our study population may reflect methodological limitations inherent to cross-sectional survey designs.

The current smoking prevalence in our study population was 29.4%, while the minimal representation of recent quitters (1.02%) reflects persistent challenges in smoking cessation, particularly among individuals with comorbid mental illness13. Our finding that 56.3% of current smokers exhibit clinically significant depression (PHQ-9 ≥10) aligns with longitudinal evidence demonstrating smoking’s role in both depression etiology and maintenance14,15. Notably, recent quitters exhibit even higher adjusted depression prevalence (25.94%; 95% CI: 12.95–38.93) compared to current smokers (20.01%; 95% CI: 17.02–23.00), with 2.89-fold elevated odds (95% CI: 1.15–7.25) after controlling for sociodemographic factors. This paradoxical association underscores nicotine’s self-medication properties in acute depression relief16, while the residual neurobiological effects of smoking cessation may increase vulnerability to depressive relapse17. Moreover, a shared genetic risk architecture between nicotine dependence and major depressive disorder has also been noted18. The strong association between smoking and depression in our analyses may reflect complex temporal relationships, though cross-sectional data preclude causal inference, creating a maintenance cycle difficult to disrupt through cessation alone.

Our exploratory analysis in lung cancer patients suggested current smokers had higher depression prevalence than non-smokers (16.82% vs 4.12%; p=0.0008). However, small sample size and potential residual confounding require cautious interpretation. This association persisted after adjusting for sociodemographic confounders, suggesting behavioral or biological pathways warranting further investigation. Notably, independent analyses showed females had a 2.18-fold higher likelihood of depression than males, and young adults (20–39 years) had the highest depression prevalence (25.16%). This suggests young female smokers may represent a vulnerable subgroup, though direct interaction testing was not performed. The 4.1-fold odds of depression among smoking patients may reflect the direct neurotoxic effects of smoking on serotonergic pathways6, psychosocial stressors from stigma and social isolation, or reversed causation where pre-existing depression impedes cessation efforts19.

Our findings reinforce the need for integrated oncology-psychiatry care models. While smoking cessation remains the cornerstone of lung cancer prevention, attention to mental health sequelae is needed as we identified 2.89-fold elevated odds of depression in recent quitters. Moreover, longitudinal evidence links depression to higher mortality in early-stage disease20, and sex disparities in treatment adherence21. The 25.2% depression prevalence among young adults in our sample (20–39 years) may imply that screen-and-treat protocols should extend beyond traditional oncology settings.

Limitations

Our study has limitations that warrant consideration. The cross-sectional design precludes causal inference regarding the smoking-depression-lung cancer triad. Self-reported lung cancer diagnoses may underestimate true prevalence due to survival bias and lack of histological confirmation. Residual confounding from unmeasured variables – including secondhand smoke exposure, alcohol use, physical activity, body mass index (BMI), urbanization, and genetic susceptibility – persists despite multivariable adjustment as these factors are established depression risk predictors22-24 and may confound the observed associations. The US-specific healthcare context may not reflect settings with different healthcare systems, and NHANES sampling excludes institutionalized populations, potentially underestimating severe comorbidities. Absence of formal mediation analysis limits causal interpretation of smoking’s mediating role.

Despite these limitations, the nationally representative data and structured mental health assessments provide robust population-based evidence. Future research should conduct multinational cohort studies to examine cultural modifiers, implement causal mediation analyses with time-varying exposures and potentially integrate multi-omics data (e.g. epigenetics) to elucidate biological pathways. Moreover, future studies should adjust for physical activity, BMI, and urbanization in depression-smoking models.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite methodological constraints, this study indicates that recent smoking cessation (<1 year) is associated with higher odds of depression. Current smokers have greater odds of depression compared to non-smokers. Among lung cancer patients, smoking shows a preliminary link to depression burden. Integrated interventions should focus on depression management during cessation, especially for females and young adults.